The Scars of Uvalde (Men’s Health)

(2024 National Magazine Award Finalist, Profile Writing)

The children laugh and move in buoyant, colorful streams. They parade through the hotel lobby out into the bright morning smog, jostling and bouncing off one another. They wear Mickey Mouse ears and giddy grins of anticipation. They lead a line of parents pushing baby strollers past stuffed animals and cartoon backpacks. They fill the sidewalks, heading toward the happiest place children know. They are heading to Disneyland.

The doctor walks against the tide of happy children, moving through the lobby toward the convention center. The children pass around him, and as their laughter fades into the street, the doctor finds himself floating among the business attired. They amble toward the arena, the 2022 meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. They wear blue and white badges. Many carry poster tubes of research.

They gather around the arena now, where the speakers are about to begin their keynotes. The doctor makes his way to the backstage entrance. He will be the last to speak. He is honored to speak here, and yet he would rather be anyplace else. He does not feel like the hero some say he is, and he reminds those who ask: He did not save anyone that day. …

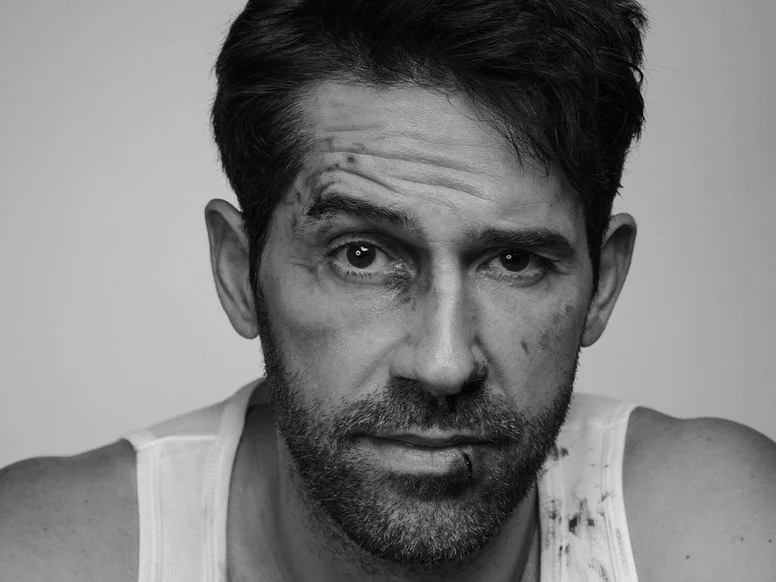

Scott Adkins Is … THE GUY FROM THAT MOVIE! (Men’s Health)

FADE IN: BIRMINGHAM, ENGLAND — 1989

A FLASHBACK SCENE:

We open on a boy. He is 13. Dark wiry hair. His body, lean. His smile, a mischievous grin. We see him boarding a bus with his mates. We see him standing in the back with his mates when some men get on. Robbers. They make for the boys. They turn them around, frisk them, take out their wallets. The men don’t have weapons. They are just older, bigger. One robber, taking out the boy’s wallet, catches him grinning.

ROBBER #1: “Why are you smiling?”

BOY: “I’ve never been robbed before.”

[A pause]

BOY: “It’s kind of cool.”

ROBBER #1 just looks at the BOY, and then—WHACK! —punches the BOY in the face.

J.K. Simmons Played the Long Game, and Won (Men’s Health)

You him on page 166 of the 1970 Thomas Worthington High School yearbook. It's the kind of high school interchangeable with every other American high school—the same brick, the same tomb-like sign on the entrance lawn, the same head of some animal pasted everywhere—and the kind of yearbook, also interchangeable, where somehow each page demands a sports photo. You find him, there, in a middle row on the JV football team. The Cardinals. The boys wear shoulder pads and underneath some wear the team T-shirt, “Worthington Football” written on the chest above a ball and the team’s motto beneath: “It’s gotta hurt!”

He stands there, Jonathan Kimble Simmons. He is a freshman, with a long face and an impressive blonde mane. And he doesn’t want to be a jock anymore.

There are clear delineations in social life at Thomas Worthington High School in Worthington, Ohio: you are a jock, you are a nerd, or you are a weird hippie freak. You cannot cross these lines.

He isn’t sure how to tell his friends, but Simmons wants to cross these lines. . . .

Jim Carrey Would Like to Erase Himself Forever (Men’s Health)

It’s winter 2010 and Jim Carrey has once again walked through the door, “Truman style.” Walking through the door—the metaphor taken from Carrey’s role as the Truman Show’s titular movie star (Carrey, the movie star within the movie), which became a prophetic part both for Hollywood culture and for Carrey himself—walking through the door—happens every so often. It has become the life- imitating-art way for Carrey to express escape. From fame. From expectation. From having to play himself. Like most pathways to enlightenment, the threshold crossing can be painful; walking through the door at times means sweet euphoria and, at times, supreme hell.

So Jim Carrey is through the door once again, and, now on the other side, dragging large paint cans down the cold streets of the West Village. He’s set up an art studio here. He spends all day painting and parts of the early morning “dispatching drunks” and most hours heartbroken. He’s battled depression his whole life, was on Prozac for a time, and had since switched to a regimen of part cognitive behavioral therapy and part holistic medication—hydroxytryptophan and tyrosine, just enough to bump his dopamine—and now part painting, which is doing wonders for Carrey, because “creativity is medicine.” . . .

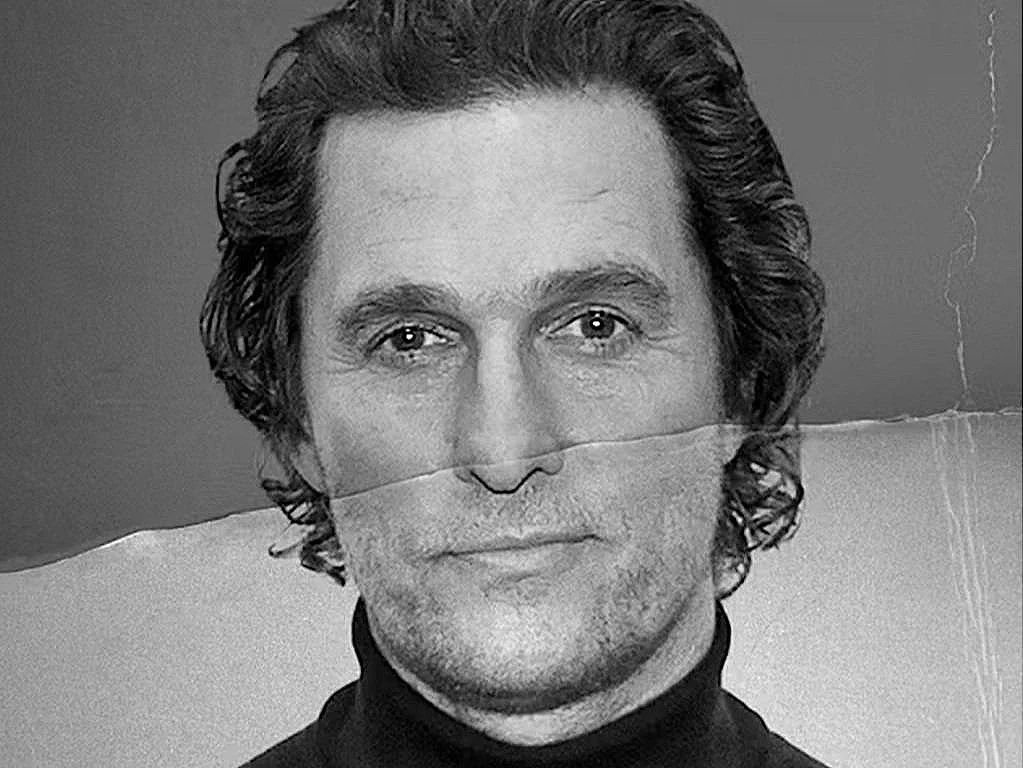

“Good Job, McConaughey” (Men’s Health)

The first of him we ever saw was a hand. Matthew McConaughey’s right hand resting open across his tuxedo buttons in a commercial for Al’s Formal Wear, in 1991. Back then, they were working hands. Playing hands. They’d built tree houses and spun truck wheels and driven golf balls far down Texas fairways. They had not yet gripped trophies or pounded bongos or worn handcuffs. They were not yet movie-star hands.

Perhaps there exists a universe in which that hand is all we ever saw of McConaughey, a universe in which that was all we remembered or judged him by. But that universe was not to be ours. In our universe, it was the face that paid the bills. It was the face by which he would be judged.

The hands are 50 now (and some change). The fingers swell around two rings—one silver and copper to protect the owner from evil thoughts, the other a wedding band. They rise now in front of the screen, when McConaughey is asked about the first time we ever saw him. “Al’s Formal Wear. And it paid 150 bucks,” he says with a grin. “My hands. They didn’t pay the rent, but they bought me a few drinks.” The grin seems to linger forever.

Long Live Derek Cianfrance, the King of Pain (Men’s Health)

Derek Cianfrance loves Mark Ruffalo’s face. He loves that his face lacks symmetry and isn’t classically “beautiful.” That the left side of his face and the right side of his face aren’t quite in sync—not since Mark Ruffalo suffered a brain tumor when he was 34—that each side still, sometimes, betrays its brother. Derek Cianfrance especially loves Mark Ruffalo’s teeth. That they are not movie star teeth. They have chips in them; they have not been straightened. Derek Cianfrance hates pearly white perfect straight teeth that are too perfect and white and seem fake. So when he films Mark Ruffalo’s face, Derek Cianfrance always uses a long lens to show more of this imperfection—because this imperfection represents everything it means to be real and human and so actually beautiful. Such is the face of Mark Ruffalo.

. . . Derek Cianfrance doesn’t yet know what all this pain really means. He’s still editing. He knows only that it is important. He knows he wants to show Mark Ruffalo first from a distance and then from up close. He wants Mark Ruffalo’s bodily pain to draw the viewers in. Then his face will keep them. His imperfection, Derek Cianfrance believes, they too will love.